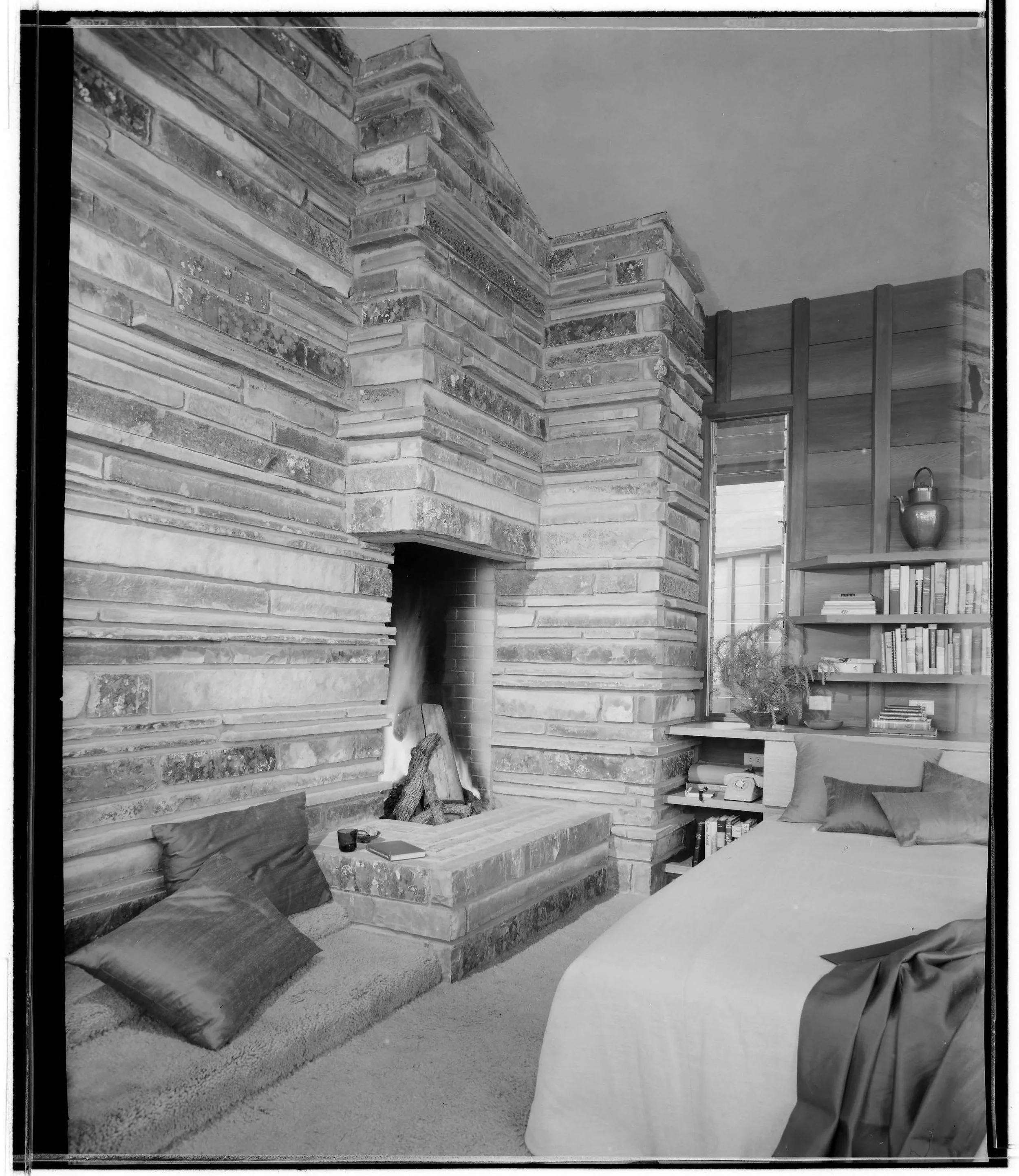

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

An oceanfront estate property of nearly 3.5 acres with magnificent views of the Pacific Ocean, Abalone Cove, and Catalina Island. One of Frank Lloyd Wright's most talented and original disciples, Green ran his own distinguished practice while serving as Wright's West Coast representative from 1951 until the elder architect died in 1959. The Anderson Residence is one of Green's finest works- an important and almost entirely intact example of his Organic Modernism. The procession of space begins with a deeply recessed entryway. Once inside, a V-shaped plan directs sharply gabled rooflines outward in two directions; they seem to float above the living space. A private bedroom wing is to the left, and the more public spaces- living room, dining room, and kitchen- are straight ahead. Sweeping ocean views reveal themselves unexpectedly. There are areas of dramatic openness; others are more intimate and withdrawn. Two guest bedrooms and both baths face northeast towards a serene and private Japanese garden. In the primary bedroom, a wall of windows frames head-on ocean views. The apex of the room's corner opens completely to the outside by way of two monumental glass doors, and a quarried stone fireplace flanks the bedside. At the opposite end of the home, the kitchen is disguised as fine furniture, blending seamlessly with myriad built-ins throughout. From a central dining area, steps follow the contour of the land down to a sunken living room with original built-in seating and architect-designed furniture. A massive stone fireplace anchors the space, with adjacent mitered corner glass walls offering unobstructed panorama.

“”True, there is a roof overhead, and there are walls and mullions supporting it. But these do not seem so much to shut it in and contain the space as to shelter it, give it definition, and suggest its use. The floor you see under-foot is a continuation of the exposed aggregate concrete pavement that is outside. The walls inside are the same as those outside. The same ceiling continued overhead. And, due to the way the glass has been set in many openings, there are not the usual lines of demarcation...the absence of demarcation stems in large part from the fact that the inside and outside have been conceived and planned as one continuous area.” - Curtis Besinger, “A House with Restraint in the Vastness of Nature”, House Beautiful, October 1963. ”

Aaron Green was born in Corinth, Mississippi, and raised in Florence, Alabama, where his father was a builder and real estate developer in the small town. Green was studying art at New York's Cooper Union School in 1939 when he first became aware of Wright's architecture. Wright, then in his seventies, was enjoying a remarkable career revival with the international praise for Fallingwater and Johnson Wax's headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin. Green completed his education as an apprentice at Wright's Taliesin Fellowship. Because of his admiration for Wright, he convinced one of his own clients to hire Wright for their house instead of him. Wright was grateful -- and impressed. The Rosenbaum house in Green's native Florence, Alabama, became a handsome example of Wright's Usonian houses.

Green is usually associated with the San Francisco Bay Area, where he worked steadily from 1951 until his passing in 2001. But immediately after World War II he worked in Southern California. The region was then experiencing a tremendous explosion of architectural creativity, including many other architects who had studied, admired, or worked with Wright. Green's work nonetheless stood out; his custom home designs were published regularly in House Beautiful magazine.

Maynard Parker Photograph / Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Moving to San Francisco, Green expanded his independent practice by designing public housing that reflected the same quality as his custom homes, even on strict budgets. He also designed professional offices, commercial buildings, schools, churches, civic centers, and internment facilities that brought distinguished architecture to the growing suburban communities of California. While continuing his active practice, however, Green took on the unique role of being Frank Lloyd Wright's associate architect. Wright had a thriving architectural office spread between his compounds in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Scottsdale, Arizona, run by trusted colleagues William Wesley Peters, John Howe, and Eugene Masselink, and staffed with his apprentices. For his many California projects, however, Wright established a separate San Francisco office with Aaron Green. It was the only one of its kind, demonstrating Wright's trust in Green. With Wright, Green worked on many of the major California commissions that flowed to Wright as his fame grew in the ninth decade of his life. Some of these visionary proposals were never built, like the Butterfly Wing bridge to cross San Francisco Bay at San Mateo. But another equally visionary project, the Marin County Civic Center, was built. Wright died in 1959 after designing it but before construction began; Green saw the project through to completion in 1969, and continued as consulting architect to the county on additions.

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

The Nature of Organic Architecture

Aaron Green's architecture is called "organic" for several reasons. Its shapes, colors, and ornament are often inspired by trees, flowers, and geology. Instead of contrasting with nature, Organic architecture usually nestles comfortably into its natural setting. More fundamentally, its designs often mirror the logical complexity, based on function, that we see in natural things. Green uses the mix of colors and surface textures in natural stone to bring visual variety to his buildings, where traditional architecture used historical applied ornament. By using uninterrupted expanses of brick, Green creates a strong rhythmic pattern to complement other natural materials. Redwood panels, intentionally left unpainted, contribute their color and grain patterns to the spaces. These varied colors and textures are carefully combined to create a rich yet balanced character to the overall space.

“

Aaron Green’s architecture is called “organic” for several reasons. Its shapes, colors, and ornament are often inspired by trees, flowers, and geology. Instead of contrasting with nature, Organic architecture usually nestles comfortably into its natural setting. More fundamentally, its designs often mirror the logical complexity, based on function, that we see in natural things.”

His hillside houses are situated on the edge of the hill, and sloped terrace walls (often of stone) echo the lines of the slope to form a base. By using natural materials, the houses relate directly to the surrounding natural setting. Interior space determines the design of an Organic house; the walls, ceilings, and floors are there to shape the space. Green often uses triangulated geometries, instead of rectilinear geometries, to emphasize this flow. Frank Lloyd Wright spoke of destroying the boxy rooms of traditional houses by creating one space that combines living room, dining room, and kitchen. Each one had its own functional character (comfortable seating in the living room, a table in the dining room, counters and cabinets in the kitchen), but they were designed to be one space. Connecting a house to its natural site included bringing the outside inside, and vice versa. Patios became outdoor living rooms. Large walls of glass oriented to outdoor views -- whether it was an intimate patio garden or a panorama of the Pacific Ocean -- brought the outside into the house. Sometimes Green would actually bring nature inside by placing a landscaped atrium open to the sky in the middle of a house, blurring the line between inside and out. Integrating built-in seating, cabinetry, and furniture as part of the architecture. The structure, spaces, and functions of an Organic house are designed together as a unified whole. Built-in couches, tables, cabinets, and bookshelves become an integral part of the structure and space.

Connection to Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright sometimes banished apprentices from Taliesin for taking outside jobs, or -- worse yet -- stealing his clients. Aaron Green impressed him from the start by bringing a client to Wright, for the Rosenbaum house in Florence, Alabama. Green continued this practice throughout their association. When Wright offered to make him a business associate in a joint office in San Francisco in 1951, one of Green's roles was to bring Wright jobs in the booming economy of California. Green first encountered Wright when in art school at Cooper Union in New York. An entire issue of the professional journal Architectural Forum published in 1938 had captured Green's attention. Though Cooper Union taught Modernism, it had not taught about Wright. Green quickly visited one of Wright's new houses nearby (the Rebhuhn house in Great Neck, Long Island) and was captivated. He joined the Taliesin Fellowship as an apprentice in 1940, working on a series of Wright projects: he oversaw construction of the Rosenbaum house, built the exhibition model of the Jester house in Palos Verdes, and brought Wright another intriguing commission for a cooperative housing project in the Detroit area. There a group of auto workers joined together to build a cooperative farm and community that would help them weather hard times in their industry. At Green's suggestion, it was to be built of rammed earth, a plentiful material on the site. The cooperative would be able to build it themselves. The war, however, ended the project. Green left Taliesin in 1943 to train as a pilot. Keeping in touch with Wright throughout the war, Green was able to provide a unique service: reporting first hand on the condition of one of Wright's greatest works, the 1923 Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. As a pilot stationed in the Pacific, Green finagled a visit to Japan shortly after the surrender, allowing him to confirm to Wright that the hotel, though partly damaged by an air raid, still stood and was in operation. In 1951 Green mentioned to Wright that he had decided to move from Los Angeles to San Francisco. To his surprise Wright proposed that they become associates and open a joint office there. Green sought new jobs for Wright, acted as a trouble shooter on challenging projects, and oversaw the building of several Wright projects. Wright, however, designed each of them.

V.C. Morris Shop, Frank Lloyd Wright. 1951 image by Julius Shulman Image © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10).

““In 1951 Green mentioned to Wright that he had decided to move from Los Angeles to San Francisco. To his surprise Wright proposed that they become associates and open a joint office there.””

V.C. Morris Shop, Frank Lloyd Wright. 1951 image by Julius Shulman Image © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10).

Until Wright's death in 1959, Green was involved with a series of well-known Wright projects, including the Walker house in Carmel, and Anderson Court shops on Rodeo Dr. in Beverly Hills. Some projects went nowhere; Green introduced Wright to tract house developer Joseph Eichler, but Wright turned Eichler down: "I'm just not interested in that kind of thing, it's too low a standard." An early Silicon Valley factory for Lenkurt Electronics was designed, but went unbuilt after a corporate merger. Perhaps the most famous unbuilt project was a graceful Butterfly Wing bridge for a southern crossing of San Francisco Bay. The visionary project that did get built was the Marin County Civic Center. Green, who had just completed a major public housing project in Marin City, was instrumental in bringing Wright and the county commissioners together. Though ground was broken for the first phase in 1960, almost a year after Wright's death, Green saw the entire project through to completion in 1969.

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Maynard Parker Photograph / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Alan Hess text originally from Palos Verdes Art Center’s 2017 exhibit "Aaron G. Green and California Organic Architecture

Cover Drawing: The Aaron G. Green Archive, UC Berkeley, College of Environmental Design

Maynard Parker Photographs / Maynard L. Parker Negatives, Photographs and Other Material, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Julius Shulman Images of V.C. Morris Shop © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10).

Special Thanks to Alan Hess